Guardian

Duet for One review – Kempinski’s combative probe into parental tensions

Orange Tree theatre, London

Tara Fitzgerald plays the former violinist in a restaging of Tom Kempinski’s play that pits patient against doctor in a furious battle of wills

Change one element in the consulting room and everything changes. In theatre, too. So this distinctive revival of Tom Kempinski’s 1980 play about Stephanie Abrahams, a former star violinist who consults a psychiatrist to help deal with her diagnosis of multiple sclerosis, is jolted by a decisive change – recasting the psychiatrist, Dr Feldmann, as a woman. Suddenly their combative weekly sessions don’t replicate Stephanie’s vexed relationship with her father but chime with memories of her mother – ardently supportive but dying young, leaving Stephanie to battle alone. Her defensive carapace is now threatened by disease.

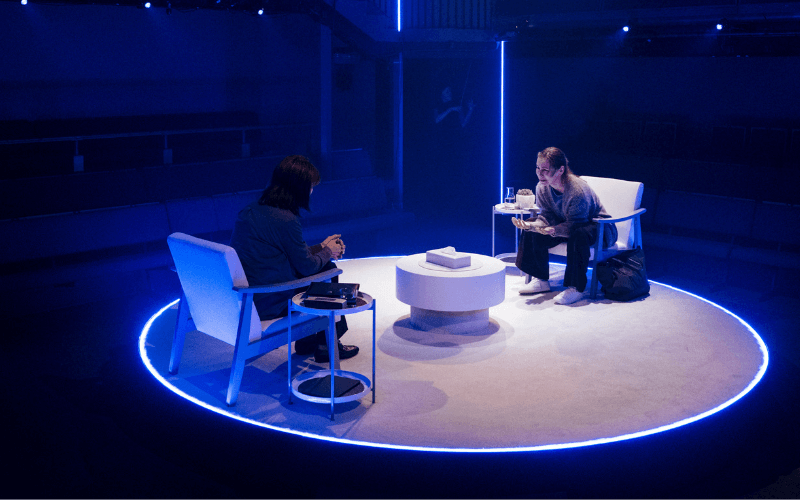

Tara Fitzgerald’s musician sits beside a squat and unrevealing cactus. Maureen Beattie’s doctor must prise open an equally unyielding patient, emotion by emotion, leaf by leaf. It could seem schematic, yet Simon Kenny’s circular stage, slowly revolving, becomes an intimate arena for their furious battle of wills. There’s a second crucial element in Richard Beecham’s production: the duet becomes a trio with a violinist who plays on the threshold of each session. Quivering, soaring, this lost and lonely sound (composed by Oliver Vibrans) reminds Stephanie of everything that gave her meaning and all she is losing to illness.

A scalding lava of unexamined feeling lies beneath Tara Fitzgerald’s corrosive growl and glare. Photograph: Helen Murray

For Stephanie, urged to attend by her composer husband (the Daniel Barenboim to her Jacqueline du Pré, though Kempinski disclaimed the connection), the sessions are a joust. She mocks, sulks, throws tantrums, but the scalding lava of unexamined feeling lies beneath Fitzgerald’s corrosive growl and glare. Beattie refuses provocation and is comfortable with silence, except for one calculated outburst at her truculent patient. Despite the Jewish director, would this excavation of parental tensions and aspirations land differently with a Jewish cast, matching the implied identities? Even so, Beattie and Fitzgerald make the air crackle. A box of tissues sits between them – only late in the play does Stephanie take one, with a slow, reluctant rasp. It suits a production that is wholly involving though no emotional cataclysm.

“There’s no magic in this room, these walls,” says Feldmann. “Just work.” The play resonates because theatre, like the consulting room, is a place to explore and debate, preparing us to live beyond its doors.