The Telegraph

4 stars out of 5

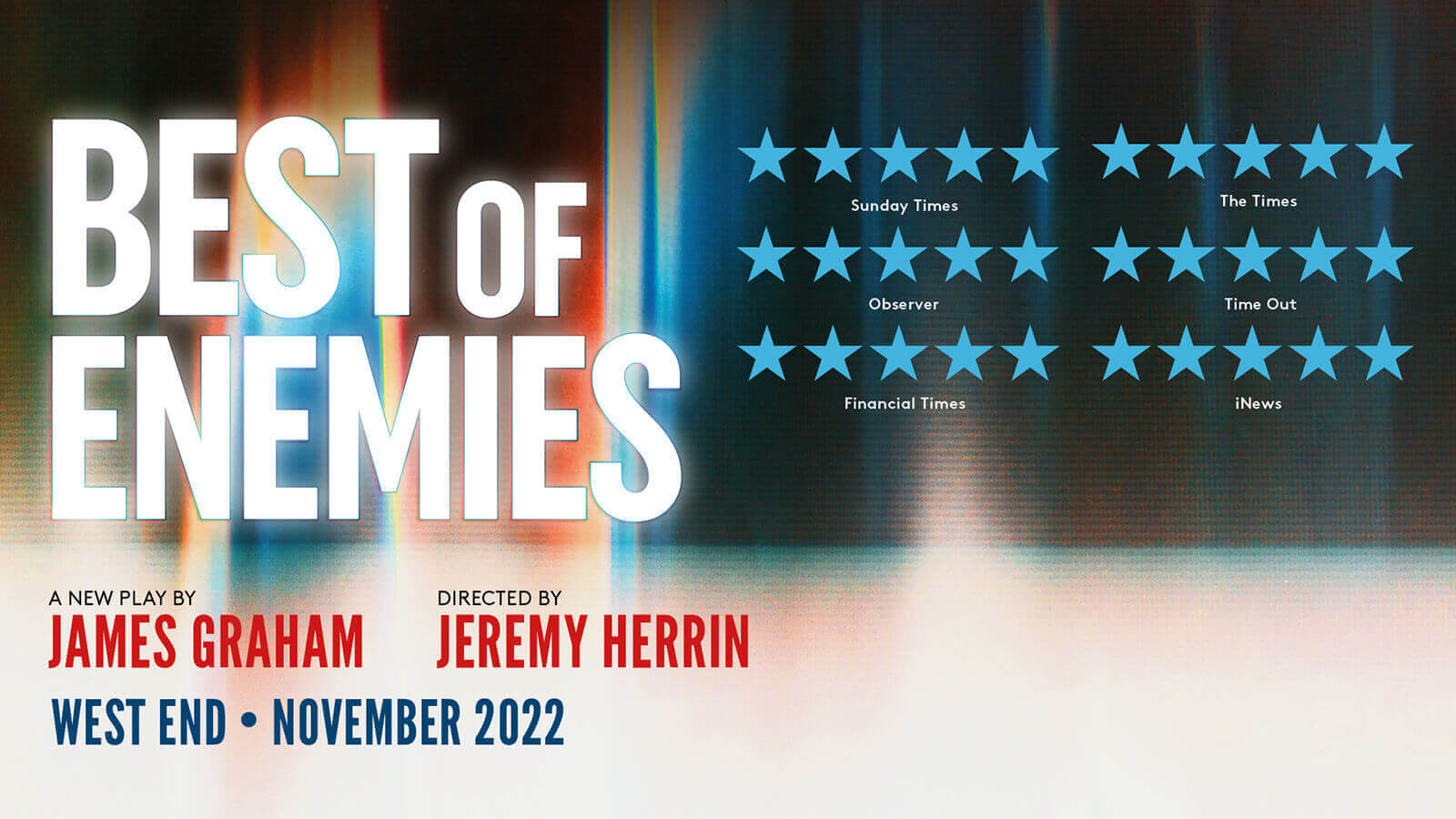

Shock and Gore: the original culture-war punch-up on stage

Best known for his Spock in the Star Trek films, Zachary Quinto is a pitch-perfect Vidal in the West End transfer of Best of Enemies

ByDominic Cavendish, THEATRE CRITIC

War of words: David Harewood and Zachary Quinto in Best of Enemies CREDIT: Johan Persson

Ding-dong merrily on high! Here’s the West End transfer of James Graham’s riveting dramatisation of the televised debates between Gore Vidal and William F Buckley Jr. The verbal slug-outs between those ornately articulate exponents of post-war liberalism and conservatism increasingly gripped America during the Republican and Democratic Party conventions, in the run-up to the presidential election, in riot-torn 1968. And do so now, thousands of miles away and half a lifetime later.

This is welcome intellectual stimulation to counter festive frivolity, and, helping to justify some steep ticket prices, Zachary Quinto – best-known for playing Spock in three Star Trek films – makes a spellbinding UK stage debut as the debonair Vidal. Quinto proves to the effete manner born in the sedentary gladiatorial bouts he undergoes with David Harewood’s Buckley. Harewood – racially cross-cast – remains a cool, commanding force to be reckoned with but (dare I say it) Quinto, in the role Charles Edwards took at the Young Vic, reincarnates his subject’s twinkling mischief to perfection.

You could josh that Quinto is bringing Hollywood tinsel to Jeremy Herrin’s snappily paced production. But in seriousness, isn’t the thesis of Graham’s piece – indebted to a 2015 documentary film of the same name – that the entertainment value of their head-to-heads, which transformed network ABC’s position, turned televised political debate into a species of pantomime? It was Buckley, deploying the word “queer” mid-outburst as a vicious slur, who shattered the civilised veneer and wound up cast as the villain. But the whole process at work, the pair realise, was calculated to stoke division.

“It was a turning point, a shift in our culture in how we talked to one another,” Aretha Franklin, no less, tells us at the start of the evening. A further transfer to New York must surely be on the cards, and it will be interesting to see whether the commentariat there, more steeped in US televisual history, buys into Graham’s argument that this episode marked the birth pangs of today’s culture wars. But it seems eminently plausible on this side of the pond – and Graham’s track record as the most astute geek on the theatrical block (a hit writer on TV, too) means you trust him to have done his homework.

If there’s a failing, it’s that almost too much research gets stuffed in, the action channel-surfing between pop-up primers, archive footage, cameos (wow, there’s Warhol!), angsty strategising and more. Filleting the 11 debates – conducted first in Miami, then Chicago, both taking in speculation about presidential hopefuls – the script doesn’t dig especially deep into the men’s backstories.

What it does do, with the physical self-composure of both lead actors a major plus, is impart an adrenal sense of two heavyweights under intensifying pressure, their battle of wits and egos compounded by vying visions for America. In the outbreaks of swirling ensemble activity and movement around them, you get enjoyable blasts of energy and nostalgia, but also a visceral, all-too-current sense of a country so in the grip of social and ideological upheaval that it’s on the brink of a total breakdown.

There’s a particular pleasure in returning to a production that you already love, a chance to luxuriate in its detail and its depth. Watching James Graham’s Best of Enemies during its West End transfer was if anything even more exhilarating than seeing it a year ago at the Young Vic. It still makes me want to punch the air.

The play centres around the 1968 TV debates between two political patricians, the conservative William F Buckley, Jnr and the liberal Gore Vidal which were manufactured by the network ABC to revive its falling ratings. Graham’s contention is that these cock-fights in the new arena of TV, changed both the nature of television and political contention forever – replacing gray balance with colourful, personalised and polarised comment.

The idea was to elevate public discourse, but it quickly fell into the gutter. That’s one of Graham’s themes that still has resonance today. But the other reason we keep looking back to 1968 is that it increasingly looks like the moment the Western world changed: Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy were shot; there were revolutionary protests on the streets of Paris; the anti-Vietnam war protestors in London and the United States were met with violence by their own country’s police. Politics failed to hold the ring and bring progress.

All of this is packed into a play and a production that has such breath-taking confidence and panache that it manages to be both highly entertaining and deeply serious as it makes the case that these debates were “for the soul of America” – and that their implications and arguments linger at the heart of politics still.

Jeremy Herrin’s production has the same bravura balance of energy and care as the writing. Bunny Christie’s hugely effective set lets three huge screens dominate proceedings; sometimes these serve as the windows into the TV studios where the executives watch the debates proceed. At other moments, thanks to Max Spielbichler’s clever video design, they show archive video footage, the live action on stage blending with the historic films of the past with uncanny precision, allowing the play literally to bring history to life.

David Harewood and Clare Foster

© Johan Persson

The supporting cast, slotting into roles as various as Andy Warhol and Aretha Franklin, are uniformly and unusually superb, their concentration on detail meaning that they play multiple parts while bringing each one to clear life. Syrus Lowe is particular fine as a mannered James Baldwin, the man who now seems like the truest prophet of the state we are in; John Hodgkinson brings rumbunctious energy both to the ABC news anchor Howard K Smith and to the ferocious Mayor Daley whose actions did so much to create the violence that destroyed the Democratic convention in Chicago. Clare Foster brings intelligence and pep to the role of Buckley’s wife.

But it is on the playing of Buckley and Vidal that the play must stand or fall. Joining the production and making his British stage debut, the American actor Zachary Quinto (still perhaps best known as Spock in the Star Trek films) is remarkable as Vidal. He exudes exactly the feline quality that Buckley criticises in his opponent: perpetually watchful and wary, slinking out of trouble with his wit. His performance deepens as the play continues, revealing the way Vidal really is shaken by the events in Chicago; you see his sudden unease and fear as he realises that a debate that “wasn’t supposed to matter” has acquired a significance far beyond itself.

But it is the casting of David Harewood as the borderline racist and unarguably homophobic Buckley that remains a stroke of genius. He brilliantly captures Buckley’s flamboyant mannerisms and tics – the way “one side of his mouth has decided to enjoy something without telling the other,” as Vidal crushingly observes. But he also tunnels into the outsider-ish insecurities that make Buckley so desire to be a banner carrier for the right, the way his wish to hold the moral high ground comes from a genuine repugnance for the left.

It’s a finely-etched portrayal in a play that is full of brilliant insight. It’s also essentially theatrical. It’s the artificiality of the devices Graham uses– including the media studies lecturer who steps out to put it all into perspective – that makes it such a visceral, thrilling experience. That makes me want to punch the air.

★★★★★

Perhaps it’s a sign of the times that the two most interesting plays in the West End at the moment look at America’s struggle to come to terms with its past. While To Kill a Mockingbird revisits the Jim Crow 1930s, James Graham’s pundit wars drama explores the moral and cultural battles of the Sixties — and unlike so many recent political plays, it tries to be fair to right and left.

If you wanted to be ultra-critical, you could point out that Jeremy Herrin’s production has lost a smidgin of its kinetic energy in the transfer from the open spaces of the Young Vic — where it opened last year — to a traditional proscenium arch. But that’s a mere quibble.

This bold and intelligent piece — based on a 2015 film documentary of the same name — still hurtles along like a sophisticated graphic novel as it explores how TV news chased ratings by throwing confrontational talking heads into the mix.

When the struggling ABC network invited the left-wing novelist Gore Vidal and conservative publisher and polemicist William F Buckley to debate each other during the 1968 political conventions, the results were even more explosive than executives had hoped.

What started as suave exchanges between two self-regarding patricians who thoroughly loathed each other turned into the verbal equivalent of a pub brawl at chucking-out time. It was ugly, undignified and, of course, a ratings smash.

If Charles Edwards was superb as Vidal at the Young Vic, the Hollywood star Zachary Quinto actually goes one better: he’s even more arch and narcissistic, preening himself in front of his male lovers and his cocktail party admirers.

David Harewood returns as the equally self-assured Buckley. It’s an ingenious piece of not quite colour-blind casting which, I suspect, will make liberal audiences think twice before dismissing his free-market evangelising out of hand.

When I saw the play the first time I worried that Harewood hadn’t caught Buckley’s feline voice. He’s still much more gruff, but given that, in real life, the two protagonists had remarkably similar speech patterns, his approach makes dramatic sense.

Bunny Christie’s vivid set places TV control booths above the action. Max Spielbichler’s arresting video design spills across the stage, while Tom Gibbons’s sound design blends a pop soundtrack with a smattering of baroque as a nod to Buckley’s love of Bach and Rosalyn Tureck.

In a multi-tasking cast, Syrus Lowe stands out as a silky James Baldwin, watching proceedings like some cynical chorus, a cigarette in his hand. John Hodgkinson is terrific, too, as the news anchorman Howard Smith and the obscenity-spouting Chicago mayor, Richard Daley, who looks on in anguish as mayhem descends inside and outside the convention hall.

Yes, the epilogue suddenly begins to preach at us. But that doesn’t really matter. Best of Enemies isn’t just a treat for political geeks: it’s a compelling human drama, as wild and unruly as the decade it brings so passionately to life.

The Guardian

4 stars out of 5

Best of Enemies review – stylish staging of a landmark TV clash

The 1968 debate between Gore Vidal and William F Buckley Jr is depicted with verve and feels uncomfortably up-to-date

Immense intelligence … David Harewood as William F Buckley Jr and Zachary Quinto as Gore Vidal in Best of Enemies at the Noël Coward theatre. Photograph: Johan Persson

Could a grainy broadcast debate between two opposing US thinkers in 1968 really have turned politics into a televisual popularity contest? James Graham’s fabulous, frenetic play concerns the clash between Gore Vidal, speaking for the New Left, and William F Buckley Jr on the New Right, in the lead-up to the presidential elections. It seems to trace a line from that moment to the birth of pugilistic, celebrity-led TV politics that feeds our culture wars, fuels Twitter’s silos and has enabled the likes of Donald Trump (as it is heavily hinted) and Matt Hancock of the jungle.

In a production directed by Jeremy Herrin, some of those associations seem strained, but this is a fascinating moment captured with immense intelligence and verve.

Originally staged in 2021 at the Young Vic and based on a 2015 documentary, this West End transfer is well-oiled and still feels enveloping and immersive. The writer has made small changes to the script, which has Graham’s wide socio-political scope and sharp humour but intellectual depth, too.

Bunny Christie’s set features glass boxes and multiple screens replaying the action as well as archive footage so that the stage looks like a giant 3D TV set come to life. It is, in its effects, TV as theatre and theatre as TV. Graham’s story rewinds and flashes back and zooms in and out from pivotal speeches, which feel like television edits and montages, all clean, clever and wondrous in their execution. The whirligig of action around the debate has a bubblegum energy with cameos from Andy Warhol and Aretha Franklin.

David Harewood returns as the rightwing conservative, Buckley, and perfects the balance between swaggering intellectual and a man with a fragile ego who must be stroked by his strategist wife. Harewood’s casting as a white American who debates with James Baldwin is striking in its inversion but his views on race are not quite given the space to give this casting greater meaning. Zachary Quinto plays his opponent with more archness than Charles Edwards’ Vidal at the Young Vic; he is all dark glances and mannered drawl, a champagne leftie with a whiff of the super-villain at first but he grows into the part and owns it completely by the end.

Both actors are restricted by the highly stylised roles they play, but they never become impersonations. That is partly because the verbatim aspect of the script contains so much genuine, articulate anger and clashing ideologies that they hold us rapt. The question of whether this game-changing debate lowered or elevated the discourse is floated in the drama. Was this a slanging match or televised intellectualism? Sadly, we know the answer to that now.

Evening Standard

5 stars out of 5

This look at the corruption of modern political discourse is dynamic and intoxicating

James Graham’s dynamic, intoxicatingly thoughtful play traces the corruption of modern political discourse back to 1968. Specifically, the adversarial televised debates between the gay, liberal writer Gore Vidal and the conservative polemicist William F Buckley Jr during the Republican and Democratic Presidential conferences that year, which culminated with the two men calling one another “crypto-Nazi” and “queer”, live, to 10 million homes.

The play’s decoding of the way politics, media and fame interact has deepened since its original run at the Young Vic in 2021. No one under 60 will remember the debates, or what Vidal and Buckley stood for, but Graham stitches them back into the wider context of the Vietnam War, student demonstrations, racial tensions and the assassinations of John and Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr, with great finesse.

David Harewood reprises his superlative performance as Buckley, finding dignity in the man’s pomposity and extravagant facial tics. That a black actor is playing a patrician, white conservative initially adds an illuminating filter to the play’s themes. Before long, Harewood’s skill and charisma supersede such thoughts.

This time he’s opposite US actor Zachary Quinto as a purringly self-satisfied, borderline-cruel Vidal – less charming than his predecessor in the production, Charles Edwards, but ultimately much more vivid. Seamlessly directed by Jeremy Herrin and stylishly designed by Bunny Christie, it’s a dazzling night out altogether.

The two protagonists are surely barely remembered here now by anyone without a freedom pass: Graham, who is 40, was alerted to their debates by the 2015 documentary, also called Best of Enemies, by Morgan Neville and Robert Gordon. But as in his current musical Tammy Faye, and his TV drama Brexit: The Uncivil War, Graham discerned the impact apparently peripheral figures could have on events.

The broad strokes of the story also chime neatly with British and American society today. Then as now, identity politics, and the right to free speech and to protest, were hot-button cultural issues. There was a gulf between young and old, the dominant parties were split, and very rich men claimed to have the poor’s best interests at heart.

The ABC network, flagging behind rivals NBC and CBS, decided to introduce opinion to neutral news but their two “public intellectuals” soon started tearing chunks out of each other. The public liked it. Their favoured parties liked it. Vidal and Buckley found that they liked it too.

Cameos from Andy Warhol, Aretha Franklin and James Baldwin offer an alternative commentary on celebrity and influence. But again, Graham is more interested in the peripheral or the forgotten than those whom history reveres. John Hodgkinson gets two great turns as ABC anchor Howard K Smith and Chicago’s autocratic Mayor Richard J Daley. Warhol, I think, gets 15 seconds of dialogue here rather than the 15 minutes of fame he predicted for everybody.

The supporting characters often morph into their real-life, filmed counterparts on Christie’s set, where glass-windowed edit suites become retro TV screens. In an epilogue, the long-dead protagonists set aside their rancour and reflect on where the ratings-driven hunger for charismatic contrarians has got us now. Again, this scene seems much more organic and moving than it did first time round. I really can’t fault Herrin’s bold, pacy production, or the canniness and flair of Graham’s writing here. Bravo.

Time Out

4 stars out of 5

James Graham’s monumental ’60s drama transfers, with tremendous performances from Zachary Quinto and David Harewood

The great thing about a James Graham play is that you go in with only the haziest ideas about the twentieth-century political moment he’s picked as his subject, but come out two-and-a-bit hours later buzzing with its personalities and conflicts and stories. And ‘Best of Enemies’ typifies that feeling, alighting on the relatively niche subject of telly debates in the run-up to the US 1968 Presidential election, and making it completely lucid and vital.

The stars? William F Buckley Jr and Gore Vidal, two American political commentators and public intellectuals who loathe each other in an enormously entertaining way, and are mercilessly lined up by the ABC telly executives who’ve spotted their potential to boost its flagging ratings. They butt heads like elk, battling for control of the unknowable snowy wilderness that is the political conscience of the average American viewer. These two men typify the emerging face of American politics. Once, it was Republicans versus Democrats. Now, it’s conservatives versus liberals, with Buckley campaigning for a New Right that mobilises the silent majority, while Vidal attempts to ride the wave of student protest and social liberalism.

It’s pretty inevitable that a theatre audience would end up siding with the latter, and that’s especially easy here: Graham digs into all of Vidal’s contradictions, exploring his half-hidden, half-open gay identity, and the way his need to be taken seriously as an intellectual fights with his urge to enthrall the public with rhetorical flourishes, pre-prepared catty asides, or the salacious sexual freedoms of his novel ‘Myra Breckinridge’. Hollywood actor Zachary Quinto, best known for sci-fi roles, steps into the role for this West End transfer. Perhaps he’s a bit of an unlikely piece of casting here but he’s utterly compelling: feline and aloof to start with, but shedding his calm like stray cat hairs once Buckley starts to get the better of him.

David Harewood returns from the Young Vic run as Buckley, making an intriguing adversary: with his moneyed drawl, he struggles to be the man of the people he longs to be seen as, and Harewood captures the odd mannerisms of this awkward political performer, licking his lips with lizard-like nervousness.

Still, casting a Black actor in the role of a white conservative does muffle the impact of Buckley’s debates with visionary Black American writer James Baldwin: famously, the two argued across America’s deep racial divides in a landmark 1965 University of Cambridge debate, with Buckley advocating for segregation while Baldwin offered a powerful indictment of white America.

‘Best of Enemies’ explores this side of Buckley’s story without really offering much insight into his racist mindset, or into the effect his interactions with Baldwin might have had on him. But that’s perhaps because ‘Best of Enemies’ is trying to do so much, trying to make this distant era sing for a British audience. Broadly drawn mini-portraits of familiar late ’60s luminaries like Andy Warhol and Aretha Franklin pop up, and historical footage flashes across the stage’s many screens.

Jeremy Herrin’s final production as artistic director of Headlong is bright, clear and well-served by Bunny Christie’s design, which beautifully echoes the rounded edges of the ’60s telly screens which relayed all this drama to an audience at home. In a way, it’s an unimaginably different time, one where TV broadcasts were a communal event, handed down to a public whose main way of responding to what they saw was by simply switching on or off (the kind of blunt measure today’s Twitter-obsessed decision-makers must dream of). But Graham makes it feel recent by showing that this is the time when personality and politics became inextricably intertwined, and hinting towards the limits of charisma and ego when it comes to actually governing a country.